Why Does KL’s Sultan Abdul Samad Building Exist Anyway

The nation’s capital of Kuala Lumpur hosts many attractive and historical landmarks that, upon closer examination, are in various stages of ruin and disarray.

As the government announced plans to restore the century-old monuments scattered along Jalan Raja and Jalan Tun Perak back to its original state, TRP takes a walk back in time to examine the fascinating history behind one of KL’s most treasured structures; the Sultan Abdul Samad building.

Conception of a national monument

Commissioned by the British in the late 1890s, the iconic Bangunan Sultan Abdul Samad stands proudly along Jalan Raja directly in front of the equally historical Dataran Merdeka.

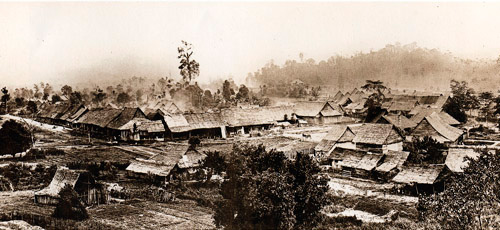

During the time, KL was nothing more than a small but bustling mining and trading settlement in the heart of Selangor.

The structure was built in order to serve as the new centralised administrative centre for the British colonial government that was originally housed on top of a small hill at Bluff Road or Bukit Aman as we know it today.

Supposedly, the then British Resident of Selangor, William Bloomfield Douglas had wanted the colonial government’s buildings and staff quarters to be located to the west of the Gombak River, away from what he deemed to be the unsanitary and rowdy populous of pre-independence KL.

(Credit: Wonderful Malaysia)

Far enough away so that the Brits would be relatively safe and prepared if the people were to rise up against their occupying masters.

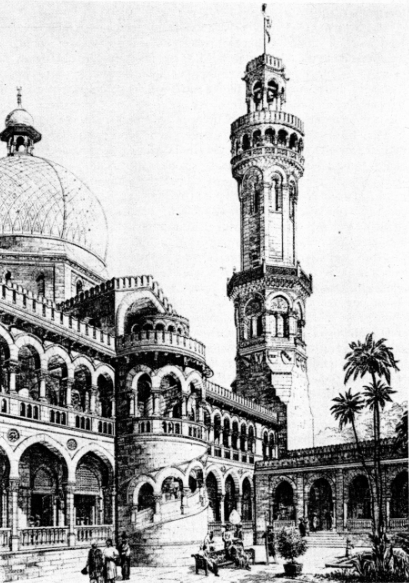

The building was originally designed in the Classical Renaissance style of early 15th century Europe by British architect A.C Norman. However, the structure was later reworked into the more quintessential Indo-Saracenic, Neo-Mughal inspired designs by Norman’s assistant, R. A. J. Bidwell and draughtsman, A. B. Hubback that stands now.

(Credit: Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society)

The two-story building is flanked by two towers, with a central 41-meter tall clock tower adorning its middle which are topped with gleaming copper domes.

The bright red bricks, white plastered arches and banding that makes up the structure of the building gives the monument a unique aesthetic some referred to as the ‘blood and bandage’ style of design.

Roughly taking on the shape of the letter “Fâ€, the building took 4 million bricks, 2,500 barrels of cement, 50 tonnes of steel, 30,000 cubic feet of timber, 5,000 pounds of copper and 18,000 ‘pikul‘ of lime (not your sirap limau lime yeah, in this case, it means limescale, a.k.a calcium carbonate) to build.

When it was completed in 1897, the structure stood as the largest building in Malaya and a grand dinner was held in its honour by British General Resident of the Federated Malay States (FMS), Sir Frank Swettenham.

(Credit: Wazari Wazir)

The building dazzled many with its tall, towering facade and was illuminated by ‘state-of-the-art’ gas burner mantles, the first of its kind in KL at the time.

The great bell tower

The Sultan Abdul Samad clock tower is also completely unique in its own right.

Designed to replicate London’s Big Ben, the Gillet and Johnston Manufacturers bell clock on top of the building’s centre tower was made in 1897 and has kept ticking and ringing every hour, on the hour for over a century

The clocked first chimed its bells the same year it was installed to coincide with the Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee parade in London.

The great clock tower echoed 12 times at the stroke of midnight officially commemorating Malaysia’s independence in August 1957.

Recently, the clock became the face of controversy when it was revealed that its caretaker for over 40 years received only an RM10 raise just weeks before he was meant to retire.

The bell clock is now maintained by a couple of volunteers adamant about preserving another great national treasure.

A witness to history

Throughout its century-old history, the Sultan Abdul Samad building had been put to many different uses.

During its early years, the building was simply known as the ‘Government Offices’ and was the home to various government departments of the colonial FMS as well as the Selangor State Government.

(Credit: SEK KEB Jambongan)

And as mentioned, the monument historically stood as the backdrop to the nation’s independence as crowds gathered at Dataran Merdeka to witness the lowering of the British Union Jack to the chime of the building’s iconic clock tower.

In 1974, the building was officially renamed after the reigning Selangor monarch during its construction, his majesty Sultan Abdul Samad, while the Selangor State Government offices were moved to its current residence in Shah Alam.

(Credit: Portal MyPT3)

Then in 1978, the structure was again renamed as the Federal Court as it housed the Supreme Court, High Court and Court of Appeals, and the building was left vacant for several years after the courts relocated to Putrajaya in 2007.

Now, the building is used as offices for the Ministry of Information Communications and Culture (KPKK) as well as a favourite spot for KL’s many sightseers and tourists.

(Credit: Le journal de Sara Lisa)

Though some of Malaysia’s iconic monuments might be old and a little outdated against the backdrop of KL’s modern skyline, these historical structures serve as a great reminder of the nation’s past, present and future heading, and should command a great amount of respect and tender care.

Share with us your favourite historical monument on our Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Typing out trending topics and walking the fine line between deep and dumb.