When Cultural Appropriation Met Hate [OPINION]

By:

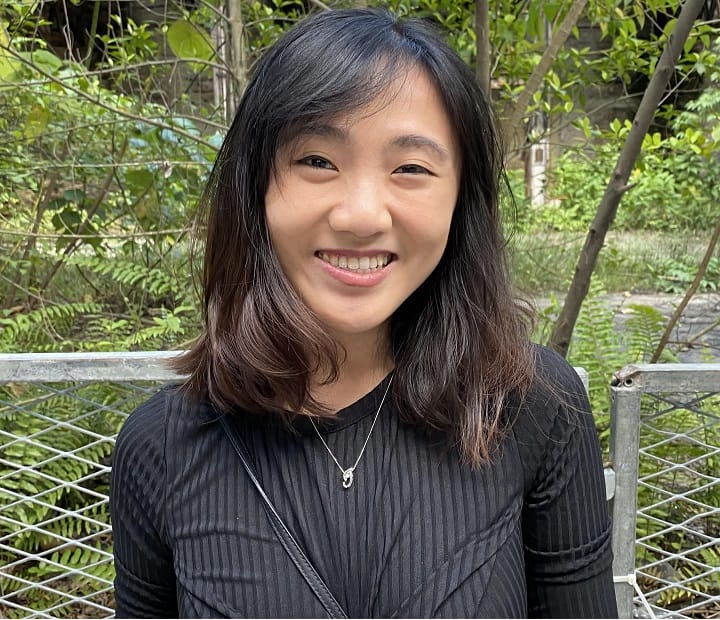

Tham Jia Vern

Researcher, The Centre

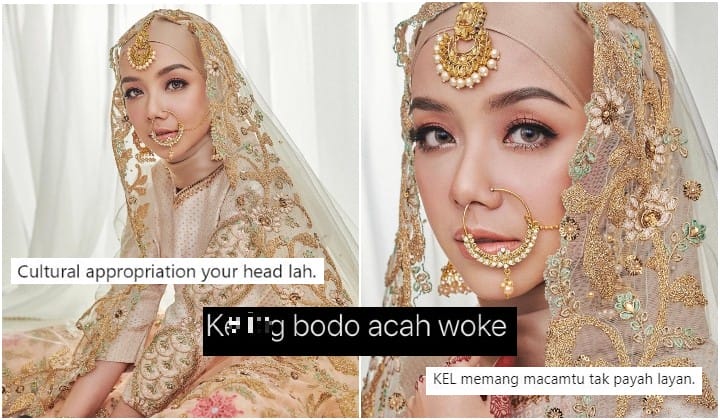

It’s been an interesting few days in Malaysian societal relations. A recent social media promotion for contact lenses featuring actress Mira Filzah inadvertently sparked controversy and heated discussion on a fairly new concept in Malaysian racial politics – cultural appropriation.

Photos of the actress in full lehenga outfit, a form of traditional clothing for Indian women, together with a lip-sync video to the song ‘Maar Dala’ gave rise to a charge that the actress was appropriating and profiting off Indian culture.

The accusation, in turn, began a wave of online debate on the difference between cultural appreciation and appropriation.

The debate was further complicated by the fact that the wardrobe for the ad campaign was provided by an entrepreneur of Malaysian Indian-Muslim descent who markets and sells ‘baju Bollywood’.

The robust debate and eventual reconciliation of this issue is a great example of how the unique multi-racial setting in Malaysia can engage with so-called Western societal concepts on our own terms.

For many, the conversation has been eye-opening. I for one am now much more aware about what cultural appropriation could look like in Malaysia and what it means to recognise the contribution of all groups living here.

Unfortunately however, this episode also revealed a seam of hate and resistance. Robust debate was interspersed with racial hate speech targeting the Indian community. The words “keling” and “Balik India” were used in numerous retaliatory tweets.

A thread of people saying k*ling. if you want to report, report la. But the list is never ending, unfortunately. pic.twitter.com/TeOAuxW6qW

— Manpreetoooo (@justdonewithyal) August 21, 2020

The barrage of hate against the Indian community, especially against those who originally called out the actress and the promotion, continued even after the actress issued a public apology over the controversy. Eshwarya, the Twitter user who first called out the ad, shared screenshots of netizens hurling racial slurs at her, before deleting her account entirely.

Could Eshwarya have been more careful in the way she approached the issue? Perhaps.

But is racial hate speech an acceptable way to disagree?

Our current research on the topic of racial hate speech (to be published soon) suggests that the silent majority says ‘no’.

Across ethnicities, the vast majority of our diverse study respondents agreed that not only is racial hate speech a serious problem in the country, it has been getting worse over time especially on social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp. Study participants can easily cite common racial slurs and hate speech examples coming from a variety of sources, from random tweets to the Dewan Rakyat.

From the focus groups we conducted as part of the study, we can also appreciate why the hate directed towards Eshwarya struck a chord with many in the Indian community. Compared to other ethnic groups, fear is a significant reaction felt by Indian respondents when seeing examples of racial hate speech targeting the Indian community.

What can Eshwarya, and many like her, do about the flood of racial hate speech online?

Some have raised the issue with Twitter and some are reporting tweets containing racially offensive or hateful words. Whether this cause will be taken up by the social media platforms is a big question.

Dear @Twitter

— KittySnow (@KittySn52889207) August 22, 2020

Keling is a racial slur, a derogatory insult…https://t.co/1yAvSbKYgt https://t.co/YbiwGNcsJk pic.twitter.com/KbXlJ8nXD4

Notwithstanding these individual actions, how we manage hate speech as a country needs to change. Malaysia’s current management of hate speech seems to be unsatisfactory for most of us.

Most of our study respondents called for better monitoring and regulation of hate speech particularly on social media platforms. Many also want to see more public education on the effect of hate speech, with more constructive responses like advice or counselling for less intense cases of hate speech expression.

Although our existing legal framework does deal with different facets of hate speech and incitement, laws such as the Sedition Act and the Communications and Multimedia Act are controversial and arguably too punitive and late-stage.

With findings from our study, we aim to develop a framework in managing increasing intensities of hate speech, including online.

In the meantime, as we approach Hari Merdeka and Hari Malaysia, let’s work harder to be more patient and thoughtful in the way we disagree with each other (and to understand cultural appropriation better).

To paraphrase Tunku Abdul Rahman, for us to find ‘real unity within our diversity’, we’ll need to put in the effort.

Tham Jia Vern is researching what constitutes hate speech for Malaysians and proportionate responses for it at The Centre, a think tank dedicated to centrist thought.

If you’d like to have your opinion shared on TRP, please send it via email at editorial@therakyatpost.com with the title “OPINION:” or through social media on TRP’s Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.