PPSMI: Why Malaysia’s Education System Keeps Switching Languages

Malaysia’s education system has always been a hot topic of discussion, be it the introduction of new subjects, changes in school uniforms or most prominently, the language of instruction.

Many of us are aware of the never-ending debate between the English language proponents and Malay language proponents, especially in relation to the implementation of the Policy of Teaching Science and Mathematics in English (PPSMI).

While the nation continues to discuss the language policies of Malaysia’s education system, we take a look the history of these policies and the reasons that drove the seemingly non-stop back and forth.

The origins of Malaysia’s language-based education system

As with almost every issue that plagues Malaysia, our language policies stem from (say it with me now)… colonialisation.

In the early 19th century, Malaya consisted of a plural society where each race or community existed side by side without any real integration but in a state of “mutual accommodationâ€.

The Malays, Chinese and Indians basically lived separate lives with their own languages, cultures and religious practices and the British policy regarding education perpetuated this divide.

They encouraged a system of social management where immigrant groups had their own space and worked in their separate economic sectors and did not intermingle much with each other. This made it easier for them to identify and manage the three separate socio-cultural communities.

The vernacular-based education system

In a nutshell, the four main types of language-based education in Malaya were; English, Malay, Chinese and Tamil.

Each of the vernacular education systems used a different medium of instruction and provided a different syllabus.

The British did not discourage the establishment of vernacular schools as this could help maintain the social cohesion. It also made it easier for them to manage the three different ethnic groups.

(Credit: Malaysiakini)

The Chinese and Indian communities spoke their own languages, financed their own schools and designed their own curriculum while majority of the Malays attended Malay vernacular schools.

The Malays were given village-based vernacular schools with up to 6 years of primary education, Indian (Tamil) schools were built mostly on the rubber estates by the colonial government and the Chinese community mostly built their own schools funded by their own wealthy merchants and guilds.

However, when the need for white collar workers in the administration arose, the British had to introduce education in English.

English schools were built by the government as well as by Christian missionaries and provided 6 years of primary education and 5 years of secondary education in both science and arts subjects.

These schools were located in non-Muslim urban areas and the students were mainly Chinese.

(Credit: Wikipedia)

There was, however, a clear disadvantage with this language-based education system.

Primary education was available in all four languages, secondary education in English and Chinese, while tertiary education was exclusively in English.

Malay vernacular schools were also set up by the British near villages that had a significant population so that they would be readily accessible to several children.

The aim of this was to keep them happy with the Malay vernacular education that included religious instruction and to keep them in their place in the rural areas.

However, not all Malays were subject to this disadvantage as the British realised that it beneficial to keep on working with the Malay aristocracy – which led to the establishment of the famous Malay College in Kuala Kangsar in 1905.

(Credit: Berita MCOBA)

The graduates of this school consisted mainly of royalty and several other talented Malays who occupied posts in the government bureaucracy and this enabled the British to keep on running the country in collaboration with the Malay rulers and aristocratic elite.

By the 1920s, the English education became highly desirable as it provided a step-up in social status. Gradually, more Malays and a few Indian students enrolled in these schools.

But enrollment was subject to if they could afford the fees and the travel to the mainly urban areas where these schools were located.

During Independence

Education was quickly identified as a key component for nation building as Malaya prepared for independence in the 50s.

(Credit: Tourism Malaysia)

Shortly before independence, the British government set up the Barnes Committee to conduct an in-depth study of education in Malaya in 1951.

The Barnes Report recommended that the Chinese and Indian community give up their vernacular schools and opt for schools with Malay as the only Asian language taught.

The goal was “‘that the ethnic minority groups gave up their mother tongue education in favour of the study of the Malay language in the primary school level, but eventually in favour of the English language at the secondary and tertiary levels.’’

At the cusp of independence, the Malaya government realised that a bilingual educational system may cause a divide among the citizens.

Therefore, the 1957 Education Ordinance proposed Malay medium schools called national schools, and schools using English, Mandarin and Tamil as mediums of instruction categorised as national-type schools.

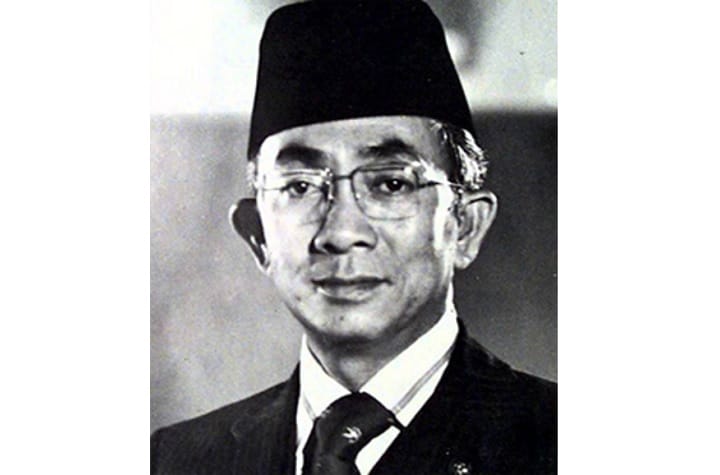

This was based on a report by a 1955 education committee chaired by then Minister of Education, Tun Abdul Razak Hussain. Subsequently, the report became known as the Razak Report 1956.

(Credit: Wikipedia)

In contrast to the Barnes Report, the Razak Report supported development of vernacular schools and proposed the following:

- existing bilingualism in the primary schools would remain

- all schools, irrespective of language medium, should use common curriculum content

The Process of Nation Building

Post-independence, Malay language was actively promoted and developed in efforts towards nation-building and attempts to foster unity in a multi-ethnic country.

The 1957 constitution declared Malay (Bahasa Melayu/Bahasa Malaysia) as the national language with special provision for the official use of English.

The government then set out on a program to establish Malay as the official language, to be used in all government functions and as the medium of instruction at all levels.

The education system was reviewed again and the Rahman Talib Report was released in 1960, suggesting that Malay language must be made into a compulsory subject besides English.

(Credit: Ministry of Education)

It also emphasised that Malay language must be taught from Primary 1 in all schools and be made the passing condition for secondary school students and teacher training centres.

These recommendations were implemented in the Education Act 1961 and the conversion process from English-medium to Malay-medium schools began in 1965.

As an interim measure a bilingual system was adopted – Malay for the arts subjects and English-medium for science and technology.

Ultimately, the goal was for the bilingual system became completely monolingual, using only Malay.

The turning point

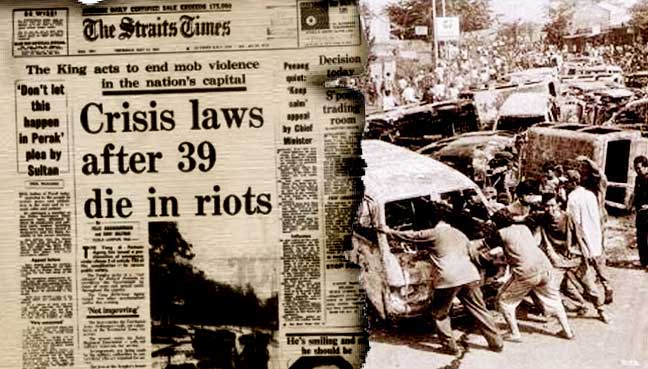

However, the real turning point for the switch from English to Malay happened after the May 13 riots in 1969.

(Credit: Free Malaysia Today)

After the explosive riots, there was a strict and rapid implementation of a national language policy.

This was based on the belief that if the status of the Malay language was not upgraded, the political and economic status of this community would never improve and national cohesion would not be achieved.

One of the main outcomes after the riots was the establishment of Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia in 1970.

It was the third university to be established in Malaysia, but the first to use Malay as the medium of instruction.

(Credit: Pinterest)

After this, all other universities were required to use Malay language as the medium of instruction, keeping with the National Education Policy 1971.

Another big impact from the riots was the declaration that all English-medium schools would be converted to Malay-medium schools by then Education Minister, Haji Abdul Rahman Ya’akub.

(Credit: Wikipedia)

The conversion began from 1st January 1970, beginning with Primary 1 until all English-medium schools up to tertiary levels would be converted to Malay-medium.

The National Education Policy was then instituted in 1971 whereby Bahasa was the main medium of instruction in schools, with the exception of Chinese and Tamil vernacular schools.

English was to be phased out as the medium of instruction and relegated to a subject in the school syllabus and taught in all schools as a second language.

In 1983, after eighteen years, all subjects including the sciences were taught in Malay in all public schools and universities.

The Rise of PPSMI

In 1993, the first attempt to reinstate English as the medium of instruction for science and technology was made by then Prime Minister, Dr Mahathir Mohamed.

However, this was met with tremendous resistance and the proposal was scrapped.

(Credit: Shafwan Zaidon/Malay Mail)

But Dr Mahathir bided his time and in 2002, he made the sudden announcement of a reversal of policy – calling for a switch to English as a medium of instruction for science and mathematics at all levels (aka PPSMI).

The factors impacting this decision included the effects of globalization, human resource development, tertiary education standards, access to science & technology and the declining standard of the English language in Malaysia.

Within 6 months of the announcement, PPSMI was implemented at Primary 1, Form 1 and Lower Form 6.

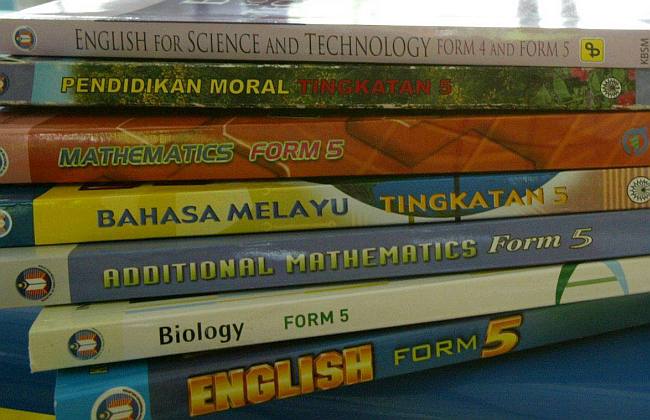

(Credit: The Star)

The Ministry of Education felt that it was urgent that these subjects be taught in English in order to equip the students with the necessary knowledge and skills in order to compete effectively internationally.

Beginning 2003, all science and mathematics-based courses were taught in English.

The Fall of PPSMI

Then in 2009, the cabinet announced that these two subjects would be taught in Malay language in national schools and in the vernacular languages in Chinese and Tamil schools from 2012 onwards.

The reversal of this policy was in part due to widespread opposition from many quarters and empirical studies that showed PPSMI disadvantaged certain groups of students, lack of time to train teachers as well as the failure of the PPSMI to improve English language proficiency among students.

(Credit: jebatmustdie.wordpress)

Several nationwide studies also painted a dismal picture of the policy’s effect on students.

A team of 50 lecturers from 7 public universities released a paper that concluded PPSMI had been detrimental to students, especially in rural areas. They noted that in a few states – for example Perlis, Kelantan, Sabah and Sarawak – students who failed Mathematics and Science subjects exceeded 50%.

Another research conducted by Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris (UPSI) found that 70% of the students from the primary schools ‘do not/barely comprehend’ their teachers’ teaching of Mathematics while 80% ‘find it difficult/fairly difficult’ to learn Mathematics and Science in English.

In addition to that, researchers noted that the gap between urban and rural schools’ performance in the two subjects had grown wider after PPSMI was implemented.

(Credit: Yusof Mat Isa/Malay Mail)

So after 6 years of implementation, the contentious PPSMI was abolished in 2012.

The reversion to Malay language for the subjects took place in stages, from Primary 1, Primary 4, Form 1 and Form 4 in 2012. Vernacular schools would teach these subjects in either Chinese or Tamil.

The changes did not involve Form 6 and Matriculation students. All exams for Science and Mathematics also remained bilingual until 2014 to avoid jeopardising the performance of students under PPSMI.

However, the Education Ministry was fully aware of the importance of the English language.

While PPSMI was abolished, a policy of dignifying Bahasa Melayu and strengthening English language usage (MBMBI) was implemented at the same time.

(Credit: Mukhriz Hazim/Malay Mail)

Wait… PPSMI Rises?

For a decade, it seemed all quiet on the Western front until current Prime Minister and acting Education Minister Dr Mahathir made the shocking announcement (again) to revive the policy of teaching Science and Mathematics in English in January 2020.

According to Malay Mail, he said it was crucial for the two subjects to be taught in English as that was the native language for both disciplines.

(Credit: The Star)

Following this announcement, several ministers have quipped in to clarify that the decision to reinstate PPSMI is not yet final and that discussions on implementing the policy is still ongoing.

While the government decides on the future of the nation’s educational language legacy once again, it’s interesting to note that researchers describe Malaysian language policy and planning process as “top-downâ€.

This is due to ‘‘policies that come from people of power and authority to make decisions for a certain group, without consulting the end-users of the language.â€

Share your thoughts on PPSMI and the education system’s language policies on TRP’s Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram!

She puts the pun in Punjabi. With a background in healthcare, lifestyle writing and memes, this lady's articles walk a fine line between pun-dai and pun-ishing.